Information International’s Round-Table Discussion - New Rent Act: Problem, Crisis and Solution

Dr. Mohammed Moughrabi’s intervention focused on four main areas: Rent Acts, the emergence of the problem, the new Rent Act and the solution.

Rent Acts

- Resolution no. 19 L.R. issued by the French High Commissioner on January 26, 1940 (Official Gazette, Issue no. 3761 dated February 29) was the first recognizable law in this respect. It gave tenants the right to extend their lease agreements unilaterally for one year only, under the prevailing conditions.

- On December 28, 1940, the French Acting High Commissioner issued Resolution 368 L.R. (Official Gazette, Issue no. 3858 dated February 5, 1941), extending lease agreements until the end of 1941, without the need for any action on the part of the tenants, and raising the rental fees of commercial and industrial shops.

- The Rent Act was later extended or new rent acts were issued which were also subject to several extensions. Act no. 160/1992 was the last among those, and its final extension expired on March 31, 2012.

- Of the provisions not contrary to the Rent Acts is Article 597 of the Obligations and Contracts Law, which stipulates that the lease agreement shall not be terminated upon relinquishment of the premises’ ownership, whether the disposal is voluntary or obligatory. Article 598 of the same law establishes that the new owner/landlord can only evict the tenant if the latter does not have a written lease agreement with a correct date, meaning that the new landlord must abide by the previous lease agreement devised by his predecessor, even if the property ownership had been transferred forcibly.

- Under Article 598 and with the legal extensions of the lease agreements over 74 years, the tenant would have thus acquired an in rem right over the dwelling, similar to the right of investment currently in force, without the need for any legal text. His right could even border on usufruct entitlement.

- To further attest that the rental right has become an in rem right, Act no. 159/92 amended Article 543 of the Obligations and Contracts Law, dictating in its third paragraph the registration of lease agreements exceeding three years and not falling under Act 160/92 at the cadastral registry so that it could be applied to third parties.

Emergence of the problem

Not all lease agreements date back to before 1940. As a matter of fact, people continued to erect and rent out buildings under the successive exceptional rent acts and the ensuing rental fees were therefore arranged and agreed upon equitably, by the mutual consent of both the landlord and the tenant and the rent was set at 10% of the dwelling’s value. If, for example, the value of the dwelling stood at LBP 50,000, the rent would then be LBP 5000.

May 9, 1967 marked the issuance of Act no. 29, which extended the previous lease agreements, excluding luxury residential buildings, which were not to be evicted before five years of the commencement date of the lease unless in exchange for a compensation. However, Act no. 10/1974 dated March 25, 1974 effectively eliminated the exclusion, extending all lease agreements signed or extended prior to its issuance. And the depreciation of the Lebanese currency only added insult to the injury to the detriment of both the landlord and the tenant.

What’s in the new Rent Act?

A highly distinctive feature of the new Rent Act is that it grants the landlord a property restitution right entitling him to recover his property for demolition purposes, for family exigency or for any other necessity. The Act distinguished between those who rented their premises before the Act 29/1967 and those who did so after this date, granting the latter half the compensation given to the former.

For a family exigency: A compensation equivalent to the rental cost over four years on the basis of the specified free market rental value, meaning 20% of the rented unit’s value for tenants before Act 29/1967 and 10% for tenants after this date.

For demolition purposes: A compensation equivalent to the rental cost over three years on the basis of the specified free market rental value, meaning 30% of the rented unit’s value for tenants before Act 29/1967 and 15% for tenants after this date.

For any other reason: A compensation equivalent to the rental cost over three years meaning 15% of the rented unit’s value.

The foregoing compensations are reduced by 1/9 with every subsequent year.

However, the previous Rent Act no. 160/92 set the compensation to be paid for the evicted tenant in the case of property demolition or recovery at 35% to 50% and court rulings put it at no less than 40% on average. Therefore, the essence of the new Rent Act is not restricted to raising the rental fees to 5% of the unit’s value within 6 years- although the percentage stands at 2.5% at best in most countries around the world- but also making the eviction of the tenant possible in return for a derisory financial compensation in the most rapid manner.

Moughrabi proceeded to explain that in the past the landlords sold their property at the market price that reflected the effect of the exceptional rent acts, at approximately one fourth of its price on the grounds that it was occupied. This effectively means that the new landlords to whom the property was handed down at a moderate cost are practically not affected- but are, rather, beneficiaries- because the new Act will enable them to evict old tenants in exchange for a trivial sum of money and to level their units to the ground and then raise the prices of their property to three times its value at the time of purchase.

Since this exorbitant profiteering is not enough for landlords, the Construction Act also allows them to double the price of their property again by amalgamating the small plots between 300m2 and 600m2 into one plot of nearly 1000 m2 to 1200 m2 or more, as per the easement zone. The Act also allows the construction of high-rise buildings of at least 18 floors, and the subdivided flats are sold to major investors, most of whom do no reside in Lebanon or are not Lebanese in the first place.

The foregoing is best exemplified in the Mina Al-Hosn neighborhood. Its local people were forced to move and the old buildings demolished, replaced by skyscrapers where nobody lives.

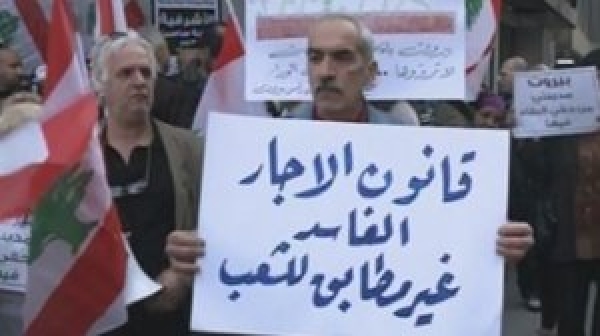

Should the Rent Act be signed, established tenants in Lebanese cities will probably be stripped of their human, constitutional and legal rights and encounter a similar fate to that of the approximately 10,000 residents of Mina Al-Hosn who have all disappeared from the neighborhood.

Solution

- Operating a cheap public transport network that allows people to live just one hour or less away from the city and thus be able to easily commute to work daily. The diverse means of telecommunications and services can even enable people to work from many locations outside the city.

- Keeping the accommodation costs at no more than 20% of the salary.

- Entitling the tenant under Act 160/1992 to buy the dwelling he has been renting at 50% of its real price. If he fails to use this right within a certain period of time, the landlord can use the dwelling without providing any reason for eviction, in return for a compensation that amounts to roughly half the dwelling’s value. Either way, the state offers established landlords compensation equivalent to 10% or more of the dwelling’s real value along with the sum of money they obtain from tenants.

- Permitting banks to fully finance these operations via long-term installment loans (15 to 25 years) at a subsidized interest rate not exceeding 2% and allowing for securities’ settlement at the Central Bank (BDL).

Dr. Nazih Mansour

Former MP, Dr. Nazih Mansour highlighted the work of the ad hoc parliamentary committee within the Administration and Justice Committee, which toiled more than 10 years to only end up devising a Rent Act that failed both to be consistent with the spirit of the constitution and to take into account both the landlord and the tenant. “Upon examining the Rent Act, one must dissect the law and analyze its components to detect the degree of its objectivity at the constitutional, social and political levels,” noted Dr. Mansour, emphasizing that the Rent Act that has been approved recently in Parliament will have several implications in terms of the displacement of low-income people, particularly the elderly who had lost their sources of income and cannot bear extra financial burdens.

Dr. Mansour regretted the transformation of the rental saga into a conflict between landlords and tenants because both of them are in his opinion victims of the extemporaneous policy of the state, which he held accountable for the current rental crisis and which he urged to solve the predicaments that the new Rent Act has created. Of the solutions that Dr. Mansour proposed:

- Benefiting from BDL’s financial reserve to grant housing loans at subsidized interest rates from a new housing institution since the Lebanon Housing Institute has become a broker between banks and borrowers and relinquished its real functions.

- Benefiting from the state property so that it can provide for residential projects for low-income segments.

- State expropriation of the properties rented by Lebanese nationals in return for insignificant sums and re-renting them out at rates that take into account the personal circumstances of every tenant.

Dr. Mansour criticized the proposed fund deeming it a fictitious one that may transform into just another source for squandering public money, especially that it is not based on proper statistics and research addressing the size of the problem, the number of old tenants and the reality of rented buildings.

Hassan Nsouli

Representing the Syndicate of Landlords, Hassan Nsouli urged a clear determination of the Lebanese economic system arguing that the system, which is largely free, becomes market-oriented when it comes to rents only. “It is established that any agreement is a function of mutual consent between the concerned parties. As far as the old lease agreements are concerned, this consent has expired 83 years ago but through inequitable laws, the state has confiscated the landlords’ properties in favor of those tenants who pass down the dwellings to their sons and grand-sons,” he added. Nsouli also drew attention to the fact that the old rented buildings have become uninhabitable and might collapse any time because the landlords are incapable of renovating and maintaining the buildings with the negligible rental fees they obtain, urging the liberation of contracts on the grounds that however long the tenant resides in a certain dwelling, this does not qualify him to occupy the residence permanently nor does it legitimize his occupation. He finally commended the Saudi model of contract liberation, suggesting that such a model can lead to reduced prices, one of the advantages of the new Rent Act.

Zaki Taha

Mr. Zaki Taha, representative of the Association for Defending Tenants, noted that the Rent Act would raise rents from 2.5% to 5% and argued that it has been devised at the service of banks, which could seize old buildings and replace them with skyscrapers. He also stressed that its provisions have cancelled the indemnification to which old tenants are entitled, slamming the approval of the Rent Act by a one article only, which, according to him, violates the Parliament’s by-law.

Imad Jabri

Economist Imad Jabri laid forth solutions inspired by the French system, emphasizing that the bequeathing of property must be stopped.

Ibrahim Mhannah

Actuary Ibrahim Mhannah told about his experience of renting an office at the Gefinor Building and highlighted the blatant price contradiction between what he and others used to pay, depicting how the management of the building would impose massive and arbitrary rent increases on him. Mhannah urged the formation of a foundation concerned with nursing the elderly who are renting residences to live in.

Eline Neemeh

Dr. Eline Neemeh from the Association of Landlords placed the constitution above all other considerations and counter-argued Dr. Moghrabi saying that it should prevail over all international treaties and agreements. Neemeh asserted that, contrary to common belief, the new Rent Act came as no surprise and had been under discussion since 1992. She pointed that staying at a residence for forty years and being entitled to another 12 years now, i.e. 52 years in total, should be more than enough for tenants, warning that the repeal of the law by the President of the Republic, should it happen, would bring things back to scratch.

Antoine Karam

Speaking for the Committee for Tenants’ Rights, Engineer Antoine Karam considered the right to housing and to intellectual property as sacred, pointing that the tragedy befalls both tenants and landlords alike and the solution does not reside in the proposed Rent Act, because the Act might realize what the Civil War could not realize, causing the displacement of people across all regions and sects.

Dr. Mohammad Saleh begged to differ with Dr. Neemeh’s assertion, prioritizing international covenants and treaties over the Constitution.

Leave A Comment