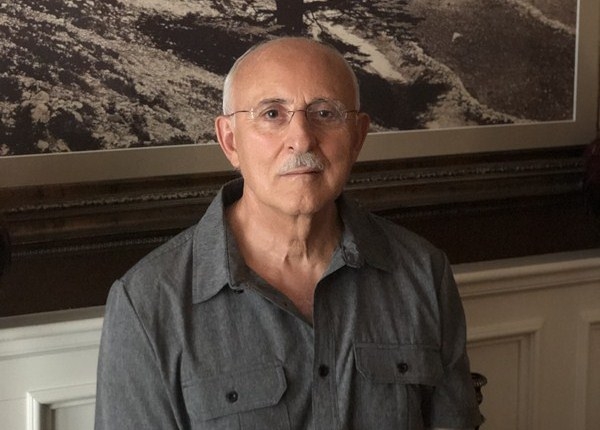

Hanna Saadah - The Municipal Elections

The Municipal Elections

Amioun, Koura

“Your mother is here to take you home,” said the school principal, Mr. Donald Dublin, as he pulled me out of chemistry class.

“But, my mother is in jail, Sir,” was my startled response as I scurried beside him through the long corridor.

“Calm down, Son. She shouldn’t see you like that,” he admonished.

“But, are you sure, Sir, that she’s been released?” I quizzed, quivering with disbelief and held-back tears.

“She’s waiting in my office and your two younger brothers are already with her.”

“You pulled them out of class too?”

“You wouldn’t want her to go home alone, would you? You and your brothers will just have to start your Easter break two days ahead of the rest of us.”

My mother struggled to stand up when we walked in but fell back into her chair and opened her arms instead. She was pale and frail but her tearless eyes brimmed with joy at seeing us well, after her four-month confinement. I was fifteen then, she was forty-five, and the year was the fateful 1961 when my father’s political party attempted a coup d'état against the Lebanese government and failed. Soon after that, my mother was apprehended, my father and his comrades were incarcerated and it was rumored that they were going to get the death sentence. My two younger brothers and I were taken in an army truck to our Tripoli Boys School, where we were boarded and ordered not to leave the premises. We had no news of our mother or father during these four, loveless months. Rumors grew more painful as time elapsed, causing us to become more reclusive until isolation became our refuge.

My brothers and I packed the few clothes we had into a big laundry bag and left the dormitory without saying good-bye to our roommates who were still in class. There was a taxi waiting at the school gate, the same taxi that had brought my mother from where she was sequestered at the government hospital to where we were sequestered at our school. Although we would have preferred to run out of the mighty, iron gate screaming, we walked out slowly instead, holding mother by the arms. The taxi driver was a man from our hometown, Amioun, who updated us on what had happened to our friends and relatives during the past four months and related the significant political developments that had transpired in our absence. Officiously, he painted a grim, frightful scene and broadcasted it into our un-questing ears. It was most merciful that the drive home took only twenty minutes.

When we arrived, we found the house door broken, nailed back together by a nice neighbor and held shut with a rope. We had to break into our own home and once in, held the door shut with a chair. The house looked like a battleground with toppled furniture, broken glass, and the contents of drawers, cabinets, and closets chaotically crowding the floor of each room where they had been spilled. Walking among the rubble and unable to find a suitable space to sit in, we made our way to the library, piled all the strewn books into one corner, and dropped down onto the oval sofa with faltering limbs and wax faces.

“I was told that they had thoroughly searched the house,” whispered my mother as if talking to herself.

“We can help you Mom,” I volunteered.

“Our bank accounts have been frozen. We need money to get started,” she muttered as she shook her head.

“I have money, Mom. I’ve been saving my allowance for the past year.”

“You have it on you?”

“No. It’s hidden in my room.”

“There’s nothing left son; they’ve opened and searched everything and everywhere.”

“But I had it hidden in my closet.”

“Oh, well, it’s surely gone then because the contents of your closet are all on the floor.”

“But the shelves are still in place.”

“The shelves? What do you mean by that silly answer?”

“I’ve pried open the front strip of the second shelf and hid the money in the space between the shelf’s two layers.”

“These shelves are solid wood. What layers are you talking about?”

“They’re fake, Mom. They’re like our doors, empty on the inside, and I’ve used that space as a hiding place.”

A faint smile colored her gray face and her eyes widened with surprise as she realized that her firstborn had his own little secrets. Refusing my help, she pulled herself up by leaning forward and pressing down on her knees. Then motioning to the three of us standing at attention around her, she commanded, “Let’s have a look.”

With smug confidence, I negotiated through the piled chaos and led the family into my bedroom. My closet doors were ajar and its shelves were empty but were still in their places. With nimble fingers, I pushed on one end of the wooden strip, causing the other end to protrude, and then I pulled the strip out. My mother and brother’s eyes glared with amazement as they peered in between the shelf layers into my secret space. Taking the wad of money out, I handed it to my mother with a triumphant air and said, “Three hundred and eighty-six liras.”

She slowly counted the cash, equivalent to about $125, and inquired with utter disbelief, “Where did all this money come from? Your pocket money was three liras a week. This doesn’t add up.”

“My father used to let me keep the change whenever he sent me to the store to buy him cigarettes.”

“And he was a chain smoker,” she added. Then, peering inside the shelf again, she asked, “And what’s this notebook?”

“That’s my secret notebook,” I confessed as I carefully delivered the notebook out and handed it to her.

She flipped through the pages with a mother’s circumspect suspicion of her teenager, frowned at me with discomposure, and then exclaimed in front of my brothers’ glaring eyes, “It’s gibberish.”

“Well, it’s written in my secret language that no one else can read,” I sheepishly confessed, enjoying my brothers’ startled aspects and my mother’s surprised look.

“You’ve invented a secret language?” She gasped with consternation.

“No, Mom. I just made up my own secret alphabet.”

She handed the notebook back to me with a sigh and said, “You’re growing up too fast my son, which is a good thing. You can take your father’s role as the man of the house, as long as he’s gone.”

I was stung by her statement: as long as he’s gone, and wondered why she didn’t say: until he returns, instead? “Did she think that my father was never coming back?” I wondered, but was afraid to ask.

Later that day, I went to the store and purchased food for my family from my own saved money. On the way back, with bags under my arms, I walked tall as if I were my father, big, strong, confident, and indomitable. I could feel the neighbors’ eyes spying me from behind curtains and some even came out on their verandas for a closer look, but no one said hello or waved. We all breathed carefully then, secret policemen were everywhere, there was fear in the atmosphere, and talking to us was tantamount to treason.

By Easter, thanks to my aunts and the few relatives who were out of jail by then, our home was restored to order and we received some money from a business partnership my father had in Kuwait. My mother, a gynecologist, reopened her clinic but very few of her patients came. It was rumored that the death sentence was soon to be handed down to many of the party leaders, and no one wanted to face a woman whose husband was on death row. Moreover, secret service men were posted at her clinic door and at our home entrance, and they took down the names of all who visited. Consequently, it took many months before her practice could eke out a living. What helped matters most was that Tripoli, being a conservative Muslim town, favored female gynecologists, especially when they were Christian, because the Koran described in poetic detail the glorious birth of Christ from Mary’s womb.

When summer came, we all relocated to our mountain town, Amioun, to escape the humid Tripoli heat. My brothers and I never went to the beach that year because it wasn’t safe for us to be in the public eye. Tensions were brewing underneath the surface between the two major political factions, those who supported the government and the death penalty for the insurgents, and those who opposed the police state and demanded that the incarcerated be treated as political prisoners rather than as common criminals. The air hissed as people argued their positions, and intimations of armed conflict during the upcoming municipal elections bit our ears like winter frost. It was a summer of discontent fomenting political unrest and reeking of violence.

My best friend Nizom and I took long walks in the olive groves, wandered among the vineyards, and had our deep political discussions far away from adult ears. The grapes would soon be ready for the picking and wine making was but a few weeks away. Except, that year, fear was on everyone’s mind because the municipal elections were to take place just before the winemaking season. Our peaceful hometown, Amioun, was destined to become embroiled in bloody conflict because the weaker pro-government faction was plotting to use its political muscle to rig the elections in its favor. Every able-bodied person was armed to the hilt and the stench of un-spilt blood was already in the air.

One day, while sitting under the shade of a large oak tree, cracking almonds between two stones, Nizom threw a pebble far away into the blue air and exclaimed, “Many a life will be thrown away just like that if the elections were to take place as scheduled.”

“But, surely, they’re doing something about it,” I reassured.

“Who’s doing something about it?” he smirked.

“The adults of course,” I replied with smug confidence.

“Salem,” he said, as he looked into my eyes. “The adults are too scared to act. We’re the town’s only hope.”

“What are you talking about? Two fifteen-year-old-kids are Amioun’s only hope? I think you’ve eaten too many almonds.”

“I didn’t mean to say that you and I are Amioun’s only hope,” he said with exasperation. “What I really meant was that you, Salem Hakeem Hawi, are Amioun’s only hope.”

“No more almonds for you,” I snapped and confiscated the pile of un-cracked almonds sitting between us.

Nizom got up and walked away without saying a word, leaving me wondering if he had suddenly gone insane. We had been friends since infancy and he was the only one who dared travel alone to Tripoli to visit us when we were boarded at our American Evangelical School for Boys, better known as Tripoli Boys School. He had always been brave, smart, and sensible but what he said that day made little sense. Knowing that he would return, I waited for him in the shade, worried, confused, and a bit frightened.

When after a very long hour he did not return, I started my walk back home with a thousand questions buzzing in my mind. As I approached the main road, I found him waiting for me by the brook. He appeared calm, reclining by the purring waters, whittling a stick with his pocketknife. I sat on a nearby stone and waited for him to say something but he didn’t, forcing me to fuel the conversation.

“Why did you walk away without saying a word?” I asked with obvious irritation.

“Because you refused to take on the responsibility of saving Amioun from bloodshed.”

“Nizom, this is paranoid talk.”

“No, you are blind to reality.”

“What reality?”

“The reality that you alone can prevent this massacre.”

After saying that, Nizom’s face became contorted with distress. Seeing how dead serious he was caused me to become even more alarmed. I still had no idea what was on his mind, but by then I was willing to listen. And so, to break down the ice that had jelled between us, I whispered with a resigned, mellow voice, “Okay. Tell me what’s on your mind?”

He took one long look at my face, and feeling reassured by my transparent sincerity, opened up his heart to me.

“Look, Salem,” he began. “Your dad is not only on death row, he is also on every lip and in all the daily papers. This, by default, makes you noticeable. Anyone who hears your name, Salem Hakeem Hawi, will know that you are the son of the political prisoner, Dr. Hakeem Hawi, and this notoriety should allow you access into the Ministry of Interior Affairs.”

In Lebanon, as in most of the Arab world, the middle name of all siblings, boys and girls, is always the father’s first name. That much I understood, but still I had no idea where he was going with his scheme, and I was afraid to ask. I remained silent and waited for him to continue.

“All we have to do is go to Beirut, find the Ministry of Internal Affairs, ask to see the minister, and implore him to cancel the elections.”

“Drop in on Minister Pierre Jumayyell, the busiest minister in the country, just like that? Are you insane? What about all the guards, secret service men, and secretaries that one has to go through in order to get to him? How do we get through all of them?”

“That’s where your name will be our passport. At every stop, you will show them your identity card and tell them that you need to see the minister on very urgent business. No one will suspect a meek-faced teenager like you of mischief.”

“And what about you? Why should they let you through?”

“Because I am with you and together we represent the Amioun Youth.”

“But we haven’t consulted with any of the Amioun youth,” I exclaimed.

“It doesn’t matter,” he growled. “For God’s sake, Salem, grow up. It’s something we can say if questioned and it happens to be believable.”

“So it’s all up to me, basically. Is that right?” I asked as the heavy weight of responsibility began to stoop my shoulders.

“It’s all up to you, Salem Hakeem Hawi,” he repeated. “Trying cannot harm, but not trying could cause so many senseless deaths and might split the town into vindictive factions for generations to come.”

I paused as tears dripped from my eyes onto the ground between my feet. Then, with an interrupted sigh, I capitulated.

“Well, what the heck, lets give it a try. If it works, we would feel like heroes, and if it doesn’t we would feel like the two fools we already are.”

We spent the rest of the afternoon discussing some important details. The cars from Amioun to the Martyrs’ Square in Beirut charged two liras per passenger and the cabs from the Martyrs’ Square to the Ministry of Interior Affairs charged half a lira per passenger. Then if we would add half a lira for a soft drink and a sandwich each, we would need a total of ten liras for the trip. Between us, we only had three liras, and that presented a big problem. Besides, our parents would never allow us to go unaccompanied to Beirut and hence it was futile to ask them for the balance because they would want to know what it was for.

Walking back to Amioun, we became morose as our plans were seriously threatened by pecuniary realities. If we had the money, we could leave in the morning and be back before sunset. We could say that we were going on a picnic and that wouldn’t be a lie—and as long as we return home by dinner, no one would miss us. All we needed was the large sum of seven liras, but we couldn’t tell anyone why we needed the money because that trip was our secret. If we were ever found out, we would be severely chastised by both political sides that were intent on fighting it out no matter what the consequences.

Despair is the father of hope because from its desperate, dark alleys new ideas sprout. At dinner, sitting around the table with my mother and two brothers, I suddenly remembered that my mother had never reimbursed me for the money I had given her when we first returned home. I waited until my two brothers left the table before I asked, “Mom, were you planning to give me back some of the money I gave you?”

“What money are you talking about, Son?” came her surprised question.

“The money that I had hidden inside my closet shelf,” I replied with a meek voice because I understood how horribly tight things were at the time.

“Surely, you don’t need all of it now, do you?”

“Oh, no Mom, of course not. I just need about seven liras because my friends and I are going on a picnic tomorrow and we need to buy a few things.”

“Oh, well then, that’s reasonable. How about if I give you ten liras a week until you are paid off?”

After dinner, with the money in my pocket, I ran to Nizom’s home and informed him that we had become solvent. That night I did not sleep. My mind was performing all kinds of acrobatic stunts, as I lay, open-eyed, blue with worry and stiff with dread. The next morning, after my mother left for Tripoli, Nizom and I left for Beirut, full of foolish hopes and in total denial of the farce we were living. We arrived at the Martyrs’ Square a little before ten-thirty and found our way among the human hordes to the cab stop. We took the two remaining seats in the service cab, which took us to the Ministry of Interior Affairs, and dropped us there at eleven o’clock.

The building was a stone edifice built during the eighteenth century while Lebanon was under Ottoman rule. Although in slight disrepair, it stood dignified like an old lion, surveying the roaring throngs that swarmed its gates. At the front door, forty steps above street level, stood two armed guards checking the identification cards of all comers, and at the lobby entrance stood another two guards who frisked all visitors before allowing them in. The lobby was a beehive with scores of people scurrying in and out, carrying folders, large envelopes, paper scrolls, and fat briefcases. Servants were running about, carrying trays loaded with Turkish coffee, freshly squeezed orange, carrot, and tomato juices, and hot coals for the purring water pipes, or argeelees. The human hum, in spite of the high ceilings, echoed like an organ out of tune into the hot, stuffy air.

After clearing the guards, we stood stunned, lost amidst this shuffling rush of humanity where everyone—except for the two of us—seemed to know exactly where he or she was going. We wanted to ask someone, anyone, where was the office of the Minister of Interior Affairs, Mr. Pierre Jumayyell, but no one noticed our pleading faces and gesticulating arms. Desperate for direction, with no signs or name lists to help us, we climbed up the wide, winding, marble stairs to the third floor where there were less people and we could converse with one another without having to shout.

“There’s an open door where we might find someone who could answer our question,” whispered Nizom, trying not to be too obvious.

“Well, should I just walk in and ask where’s the Minister’s office?”

“I think you should. There’s a cute secretary sitting behind a desk; I bet she would be glad to tell you.”

“Are you sure?” I hesitated.

“It’s the only way,” he insisted. “Come on, what are you waiting for?”

I hesitated, crossed myself thrice, and then walked in.

“Yes, may I help you?” came her clear voice as she eyed me.

“Oh, yes, please,” I replied as I gazed at her kind, beautiful face with teenage enthrallment.

“Well, how may I help you then?” she repeated with a kind smirk.

“Oh, yes, I’m, we’re looking for the Minister’s office.”

“Minister’s office?” she echoed with surprise.

“Yes ma’am, you know, the Minister of Interior Affairs, Mr. Pierre Jumayyell.”

“Oh, I see, you’re here to visit his highness, Minister Jumayyell,” she droned with a playful, supercilious tone.

“Oh, yes ma’am. It’s a very urgent matter.”

“And do you have an appointment?”

“No, ma’am, but it’s such an important matter that I don’t think he would mind seeing us.”

“Well, in that case, if you’ll tell me your name, I’ll call it in and see if he’ll see you.”

“My name is Salem Hakeem Hawi.”

“Salem Hakeem Hawi,” she repeated as she gazed at me with renewed curiosity.

I nodded without speaking.

“You’re not the son of Dr. Hakeem Hawi who tried to topple our government, are you?”

“Yes ma’am, I am. I’m his oldest son.”

“May I see your identification card, please?” she asked with a crisp, demanding tone.

I handed it to her and watched her examine it carefully. Then, becoming overtly suspicious, she asked, “And who’s with you?”

“My friend, Nizom AbuHabib.”

“Call him in,” she commanded with scrutinizing eyes.

I walked out, came back in with Nizom, and we stood at attention before her desk awaiting her verdict.

“May I see your identification card, young man,” she said as she put out her hand to Nizom.

Without saying a word, Nizom handed her his ID card, which she studied with equal scrutiny. Then she walked off with both ID cards and disappeared into the adjoining room. I looked at Nizom, who had grown pale with anxiety, and whispered, “Do you think they’re going to arrest us?”

“I don’t like how she walked away with our ID cards,” he said as he shook his head.

“If they confiscate them, we wouldn’t be able to get back home. No check point would let us through without ID cards.”

“I’m starting to feel clammy and sick at my stomach,” was the last thing Nizom said before he fainted at my feet. Feeling equally sick but not to the point of fainting, I knelt beside him and started to fan his face. It was at that most unpropitious moment that I felt a hand tap me on the head. I looked up and froze. Towering above us stood his highness, the Minister of Interior Affairs, Mr. Pierre Jumayyell.

“What happened to your friend?” he asked with a calm smile.

“He fainted, your Highness,” I quickly responded as I stood at attention.

“Why don’t you come with me then and we’ll let Miss Selma take care of him,” said Minister Jumayyell as he put his arm around my shoulder and led me into his office.

It was a modest room with a big desk and bookshelves all around. The Lebanese flag stood by the window, which overlooked the throngs below.

“Sit down, Son,” he commanded as he pointed to one of the chairs facing his desk. “If you’re coming to request permission to see your father, I can’t give it because he is in solitary confinement.”

“No sir,” I quickly replied. “I’m here to ask you to cancel the municipal elections in Amioun because we think that there’s going to be a massacre.

“Massacre? That’s a very strong word, Son. Our sources have not given us such information.”

“Oh, but Sir, I live there and I have heard the adults talk. It’s very bad, Sir. They all have ready weapons and they hate each other with passion.”

“And which side are you on, Son?” he asked as he eyed me with penetrating curiosity.

“I, Sir, am on the side of life. No one deserves to die for such a silly cause,” I said before my voice broke.

“Who sent you here, Son?”

“No one knows I’m here, Sir, no one except my friend, Nizom AbuHabib who represents the Amioun youth. He’s the one who fainted in the other room.”

“Does your mother know you’re here?”

“Oh, no Sir. She’d kill me if she ever found out.”

“Fine, Son. Go on back home and keep this secret between us. I’ll check with our sources and see what I can do.”

When I walked out, the secretary was at her desk but Nizom was not in the room. Noticing my roaming eyes, she simply pointed to the door and said, “He’s all right but must have needed some fresh air. He said he’d wait for you outside.”

I found him sitting on the long steps holding his head between his hands. Feeling equally drained, I sat beside him, and as calmly as I could fake it, asked, “What happened to you?”

“I think I fainted,” came his curt, reply.

“You think you fainted? Do you also think that you’re Nizom AbuHabib?”

“Don’t make fun of me, please.”

“Well, tell me then why did you faint?”

“My mind played tricks on me,” he said with a pale frown. “When I saw her walk away with our ID cards, I knew that they were going to take us to jail and interrogate us until we confess who was behind our visit. But, since there’s no one behind our visit but us, they would find it hard to believe and they would begin torturing us until we came up with some adult names. I was thinking of what names I should give them to avoid being tortured and that’s when I began feeling clammy and sick at my stomach.”

We arrived back at Amioun before sunset and each of us went to his own home as if nothing had happened. We told everyone that we had walked all the way to the spring of Dillah, had lunch in the café by the waterfall, and then walked all the way back. Our shoes were quite dusty from having walked all over downtown Beirut and that, plus our exhausted personas, made our story believable enough that even our suspicious mothers believed it.

Three days later, one week before the elections, it appeared in all the Sunday morning papers. “The municipal elections in Amioun have been cancelled by orders of his highness, the Minister of Interior Affairs, Mr. Pierre Jumayyell. The ministry gave no other explanation except that it would reschedule the elections at a later date.”

The next day, I accompanied my mother to Tripoli. While she saw patients at her clinic, I opened my secret shelf, took out my notebook, and with my secret alphabet wrote:

Nizom and I dropped in on his Highness, the Minister of Internal Affairs, Mr. Pierre Jumayyell, at his offices in the Ministry of Internal Affairs. We explained that due to the rising tensions, the upcoming municipal elections were going to cause a massacre if they were allowed to take place. He checked with his resources and, after due consideration, cancelled the elections.

No one suspected that we were the ones who did it and his Highness asked us to keep it a secret. The town’s people are baffled. The anti-government faction is saying that the government was afraid to lose and so they cancelled the elections. The pro-government faction is saying that the government did not wish to humiliate Amioun with one more devastating defeat.

No one will ever know what really happened except the three of us—Nizom, his Highness, Minister Pierre Jumayyell, and I.

Leave A Comment